Unhurried should be the operating system for exploring western Nova Scotia along the pretty Annapolis Valley. Enroute to an annual gathering of Class B camper vans, we took the ferry “shortcut” from St. John, NB, to Digby, NS, a town synonymous with irresistible Bay of Fundy scallops. Hugging the coastline along Nova Scotia, we slowed down, took almost a week to explore four National Historic Sites, soak in the stories of Acadie and early Canadian history, and happily exhaust ourselves discovering villages like Annapolis Royal, Wolfville and Digby.

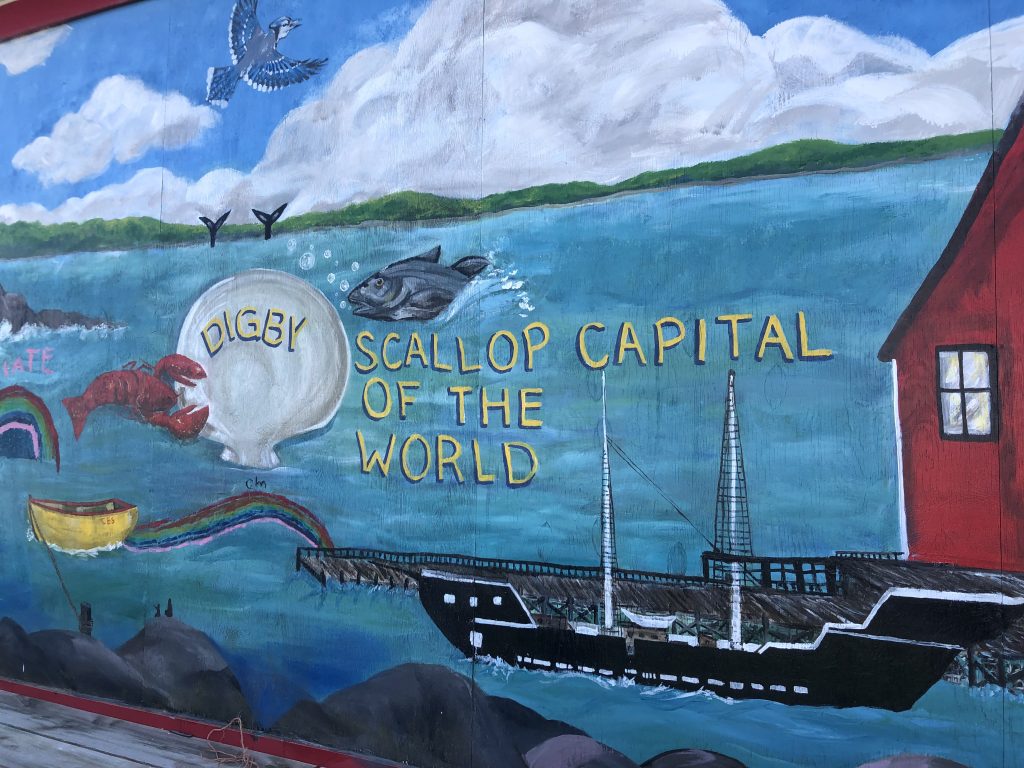

DIGBY—A SCALLOP FEAST

The ferry between St. John and Digby crosses the Bay of Fundy, where the world’s highest tides create a rich ecosystem that feeds whales and seabirds. Large fin whales, minke and humpbacks are most common—the humpbacks are known to breech and slap their enormous tails on the water’s surface. The Mi’kmaq once believed the tides are caused by a giant whale splashing.

Renowned as the “scallop capital of the world,” Digby’s Water Street was the perfect spot to stretch our legs on a short walk about town. Admiral’s Walk—along the waterfront—has perfect views over its famous scallop fleet. There is no shortage of downtown spots to find fresh scallops, cooked in every style, on the menu. The annual Digby Scallop Days festival (mid-August) showcases the town’s history and heritage.

ANNAPOLIS ROYAL—A MILITARY HISTORY TOLD

On the shores of the Annapolis Basin—which empties into the Bay of Fundy—picture-perfect Annapolis Royal is home to almost 500 people, a mix of descendants of the once-exiled Acadians, artists and retirees living the good life in rural Nova Scotia. The shores of Fundy were originally home to the Mi’kmaq people; in 1605 some of North America’s earliest European settlers arrived and established communities. The village of Annapolis Royal has many well-preserved buildings (especially along St. George Street, one of the oldest streets in North America) reflecting this history of early European settlement. The village boasts more registered heritage properties per capita than anywhere else in Canada.

The land around Annapolis Royal was a turbulent battleground between the United Kingdom and France, making it one of the most fought over pieces of Canadian soil. For more than 150 years, the region the French called Acadie and the English called New Scotland played a key role in the struggle between the two superpowers for supremacy in North America.

This centre of colonization was governed—bouncing between the British, Scots and French—from the Vaubant-style, star-shaped earthen fortifications of Fort Anne, Canada’s oldest National Historic Site, a short walk from Annapolis Royal’s main street.

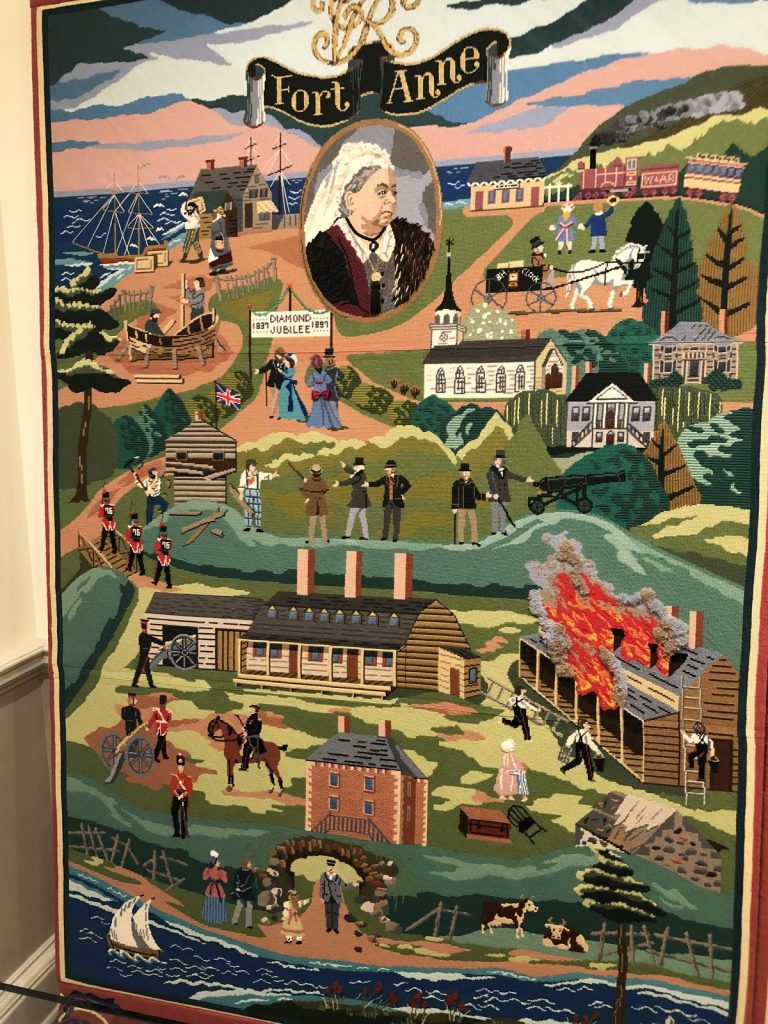

The picturesque officer’s white quarters dates to 1797 and now houses a nine-room museum chronicling the region’s history. Inside, the six-metre-long Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry graces a stone wall, telling the story of four centuries in stitches. It took more than 100 volunteers—including a stitch or two by the late Queen Elizabeth—more than 20,000 hours over four years to sew the people, symbols and events that tell the drama and history of Annapolis Royal. The materials used to create the three-million stitches include Persian wool (in 95 different colours) and porcupine quills.

Our final stop was the Annapolis Royal Garrison Graveyard which claims Canada’s oldest English-inscribed gravestone dating to 1720

Another crown jewel stop in the village is the Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens, where the impressively themed gardens include a Rose Collection with 270 varieties, the Innovation Garden showcasing what a current-day home garden could include, and a reconstructed Acadian House.

PORT-ROYAL—THE FRENCH HABITATION

Across the bay from Annapolis Royal—a 15-minute drive away—the Port-Royal National Historic Site is a reconstruction of a pre-Acadian compound begun in 1605, when the French arrived to establish a settlement on the spot. The “habitation” lasted until 1613.

Nothing original remains from the “habitation” but the site has several replica buildings—including the governor’s quarters, a common room for meals, the blacksmith shop, a small store—where we got a real feel for the small community of men who strived to learn and survive year-round. Costumed interpreters and period demonstrations recreate the look of the former French colony.

THE CRADLE OF ACADIE

To Acadians, the stretch of riverbank around Port-Royal is the cradle of Acadian settlements; anyone who’s Acadian, can trace their roots to this particular area. The immigrants from France would have considered themselves French but an Acadian is someone of French origin born here. Around 1699, after several generations, the term ‘Acadian’ began to show up in documents.

Today, millions of Acadians around the globe trace their roots to the original 500 French settlers, including the Melanson family who came to the area in 1657, establishing farms and homes. Their pioneering Acadian settlement is recognized at the Melanson Settlement National Historic Site near Port-Royal. There are no buildings remaining, but a short peaceful walk along a path took us to a viewpoint where we could see the exact landscapes that Acadian families looked out over for years.

THE LANDSCAPE OF GRAND-PRÉ

It’s a pretty, hour-long drive hopping back and forth along The Evangeline Trail (Highway 1) and the faster Highway 101 to the east tip of the Annapolis Valley, passing through some of North America’s earliest European history to Grand-Pré National Historic Site. Grand-Pré is considered by Acadians to be of huge historical significance and a touchstone of the Maritime Acadian culture.

By the mid-1700s, the Acadian community had grown to the point of establishing its own identity. The people were peaceable and determined to stay neutral in the conflicts between England and France. A tipping point came when the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain that would make them loyal to the Crown instead of being “French neutrals.”

The British considered the obstinacy of the Acadians to be a threat to the security of the colony and, in one of the nation’s most shameful tragedies, rounded up men, women and children and ordered a deportation to American communities as far away as Louisiana.

Families were torn apart, and communities were destroyed in the “Great Deportation”—a heart-breaking event of expulsion that marked Acadian history forever. Between 1755 and 1762 thousands of Acadians were loaded on boats and expelled from their homes and villages, by order of the British. Their property was confiscated. Their crops and villages were burned to the ground to keep them from returning.

The National Historic Site honours the area as a centre of Acadian settlement as well as the deportation. The quiet fields, memorial church and gardens are the Acadians’ most cherished historic site and a symbol of the strong ties that unite them. The memorial church and the statue of Longfellow’s Evangeline are symbols of the heart and resilience of the Acadian community.

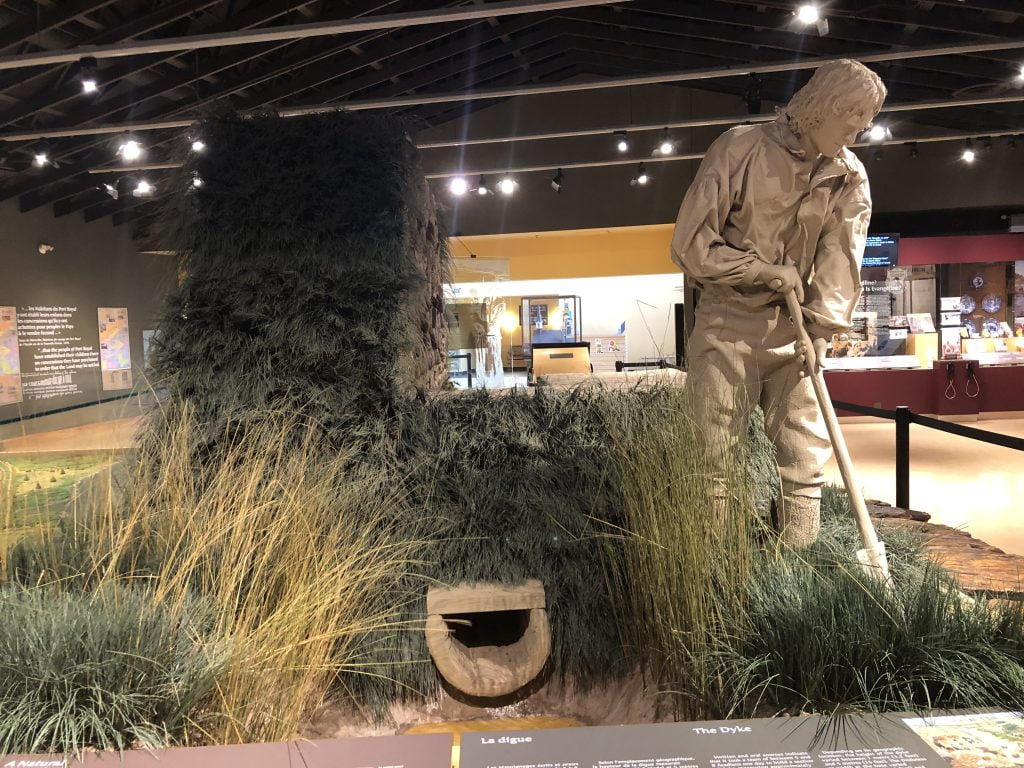

Grand-Pré is also a window to the technology of the day used by the Acadian farmers. They reclaimed the salt marshes by building tall earthen dykes with a sluice that blocked Fundy’s salty high tidewaters from flooding the fields and allowed excess rainwater to flush away the salt in the soil and flow off the dyked lands.

“Grand-Pré was known for rich, fertile soil,” explained Abbie Targett, a Student Interpreter at the site. “It was the breadbasket of Acadie. The current day dykes—now made of steel—are in the same locations and used for the same purpose. This innovative system is one of the reasons that Grand-Pré received a 2012 UNESCO World Heritage Site designation. The other reason is the importance of Acadian history and the Deportation.”

The final stop on our exploration of the Annapolis Valley was at the oft-missed overlook on Old Post Road, just above the Grand-Pré parkland. It’s a peaceful spot and a place to sit quietly and reflect on the rich history and fortitude of the Acadian people.

SIDEBAR

Where to stay:

Upper Clements Cottages & RV Park is a five-minute drive from Annapolis Royal. The RV sites can accommodate large rigs, have hookups, free Wi-Fi, an inground pool and laundromat. There are no showers . . . but the free-roaming bunnies are a highlight with kids.

We tried something different and stayed at the Parks Canada oTENTiks at Grand-Pré National Historic Site. A cross between a tent and a rustic cabin, the eight oTENTiks are a short walk from the parking lot. There is no electricity and food preparation aren’t allowed inside. Dishwashing stations and showers are available for overnight guests.